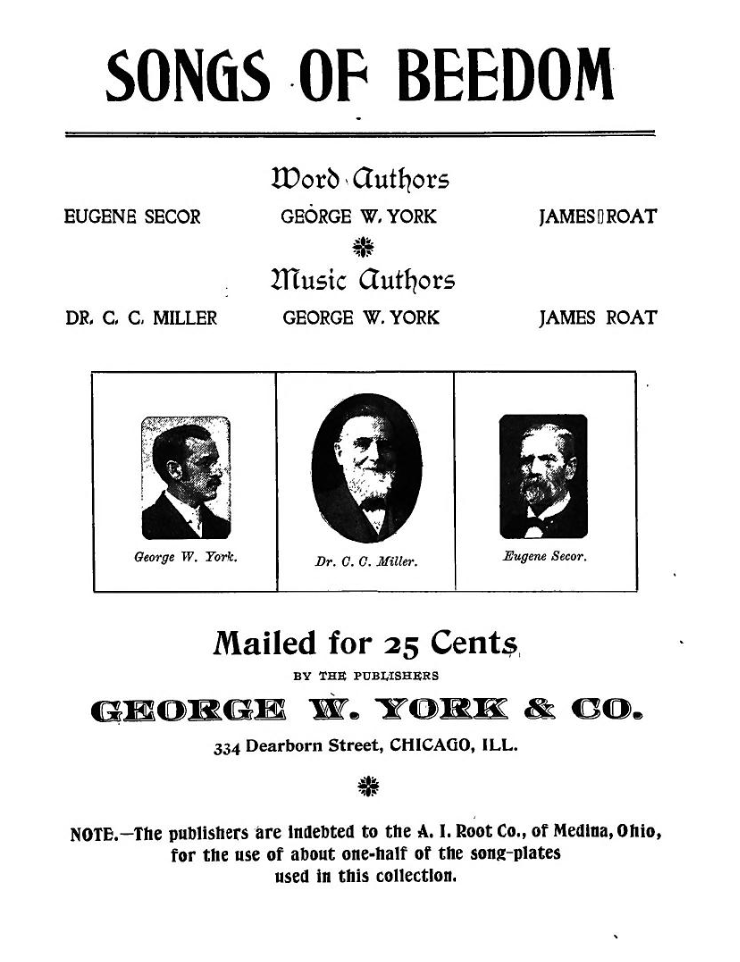

Humans and bees have long been intertwined in their lives (and their deaths) – From agriculture to society to religion, bees have been part of the story.

Humans keep looking to bees for answers and inspiration: The Fable of the Bees is a early 18th century version of Wall Street’s “Greed is good!” Drive around Utah, and you’ll see the hive everywhere, symbolizing industriousness, or, as initially was the case of the Mormons, the kingdom of God.

Unsurprisingly, bees have been wrapped up in death as well as life. And not just in their “killer” form. Nowhere is this better evidenced by the 18th and 19th century practice of Telling the Bees. In the United States (particularly New England) and Western Europe, if someone in the house passes away, the bees must be informed. You informed them? Great, now give them some time to mourn. Hives are covered with appropriately black cloth, giving the hive time to come to terms with the loss of a member of the family. There’s a whole poem about it, fittingly titled “Telling the Bees” (the fella who wrote the poem, John Greenleaf Whittier, was a pretty excellent Quaker Abolitionist, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and the writer of a poem that was incorrectly attributed to Ethan Allen for 60 years, I guess Mr. Whittier just never brought it up).

Bees handle death within their hive in their own way (no informing anyone, no mourning cloth). A small percentage of bees are “undertaker bees” – pulling dead bees out of the hive and dropping them a respectful (safe) distance from the hive. They are very quick – sometimes taking less than an hour to spot a deceased comrade and getting it out of the house. And curiously, they seem to be able to identify the dead bees by what they’re not giving off, which sounds very vibes based, but it’s not.

Bees by Sebastian. Brandt – 1580 – Wellcome Collection, United Kingdom

Bees are great. Any creature that can make a food that never spoils must be something special.