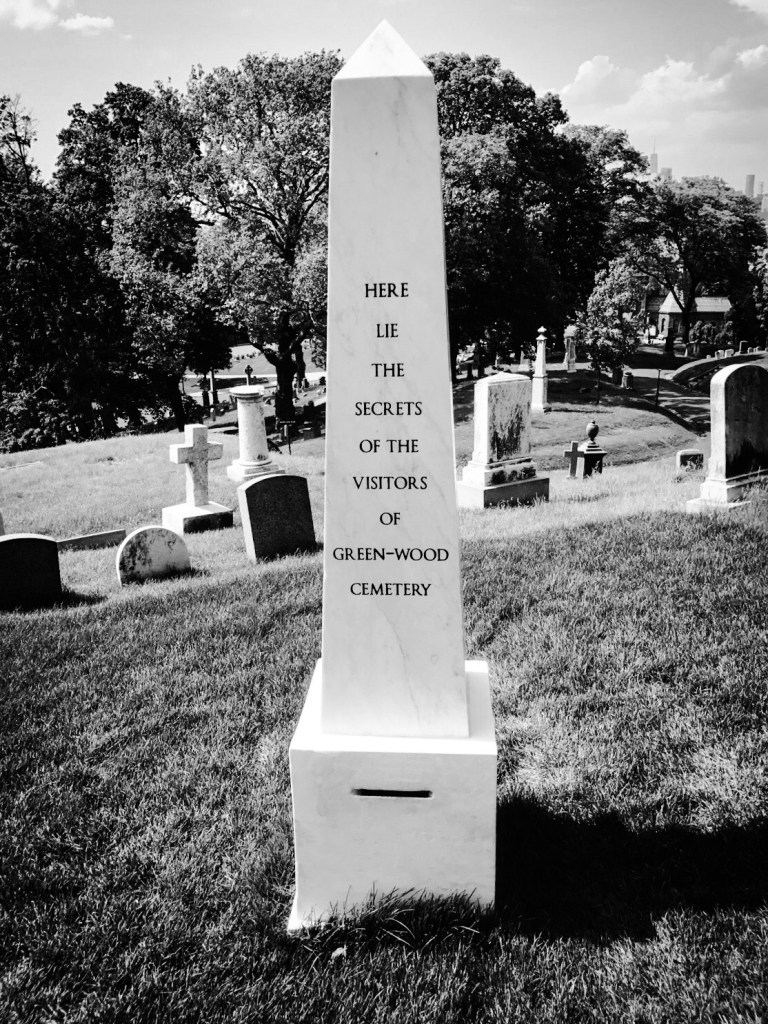

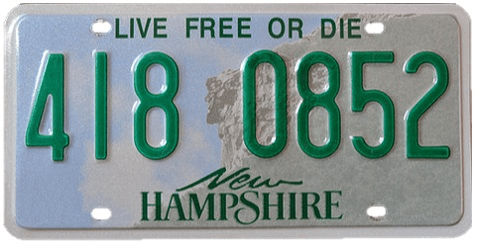

This past week I had the pleasure of traveling along the coast of New England, full of moss and cemeteries and boats and used book stores. Some vanity license plates that were a little off-putting (“GOTBO1Z” particularly stands out). And, of course, New Hampshire’s memorably license plate’d state motto Live Free or Die. Probably the most famous state motto. For good reasons, of course:

- It’s understandable

- It’s in English, unlike, say Connecticut’s Qui transtulit sustinet (which doesn’t become cooler when translated, trust me)

- A simple idea, whereas it feels like Illinois may have overreached with State sovereignty, national union

- It’s a motto. This is critical. Some states may have missed this part of the assignment. (Tennessee? Agriculture and Commerce? Really?)

- It’s catchy! Iowa, I like where you’re coming from, but Our liberties we prize and our rights we will maintain just doesn’t roll off the tongue.

- It’s an ultimatum. No other state uses the word “OR” in their motto.

Very few countries use an “OR” – ultimatums are uncommon at best. Not unheard of though.

- The French First Republic’s motto was the ambitious Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, or Death. Good luck, am I right? Also, kinda makes me think of menu options, “Sourdough, Rye, Wheat, or White? Pick ONE.”

- Somewhat related, the area of Brittany in Northwest France went with Rather death than dishonour which is good, but just suggests a preference instead of a true ultimatum. Sure, I’d rather die than be dishounoured, if I had to choose. But that’s a big “if”.

- Cuba’s got a mouthful, with Homeland or Death, We Shall Overcome! Not bad, but feels like it would help to have more details or context.

- And of course Greece, the home of philosophers and philosopher killers: Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος (Freedom or Death)

The uniquely “American-ness” of the New Hampshire motto is partly due to the simplicity of it. To compare flags and mottos: while some flags have the color red to symbolize the bloodshed that earned freedom, Mozambique put a goddamn AK47 on the flag. Live Free or Die is the AK47 of mottos. And there is a “realness” to the statement that other mottos don’t quite capture – the true corporal element to living (free or otherwise) and dying. No abstract ideal of “liberty” or concept of “death”.

Of note: In 1977 the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled in favor of a Jehovah’s Witness who covered up “or die” on his plate, claiming it violated his religious beliefs. And, according to Wikipedia, a much stupider (but related) case came up a decade later:

In 1987, when New Hampshire introduced new plates with a screened design that had the slogan lightly written on the bottom, some residents complained that the slogan was not prominent enough. One resident cut out the slogan from an older plate and bolted it on the new plate, and was prosecuted for it. The courts ruled in the driver’s favor, presumably basing it on the decision in Maynard.

Of note part II: For what it’s worth, in both 2019 and 2020, New Hampshire saw more deaths than births. FREEDOM!